Location

Mount Vernon, WA 98274

Location

Mount Vernon, WA 98274

Amid mounting climate challenges, scientists are turning underground, examining how fungal networks known as mycelial highways could boost ecosystem resilience and carbon sequestration. Emerging imaging technologies and field trials are shedding light on these hidden architects, offering a fresh avenue for climate adaptation strategies.

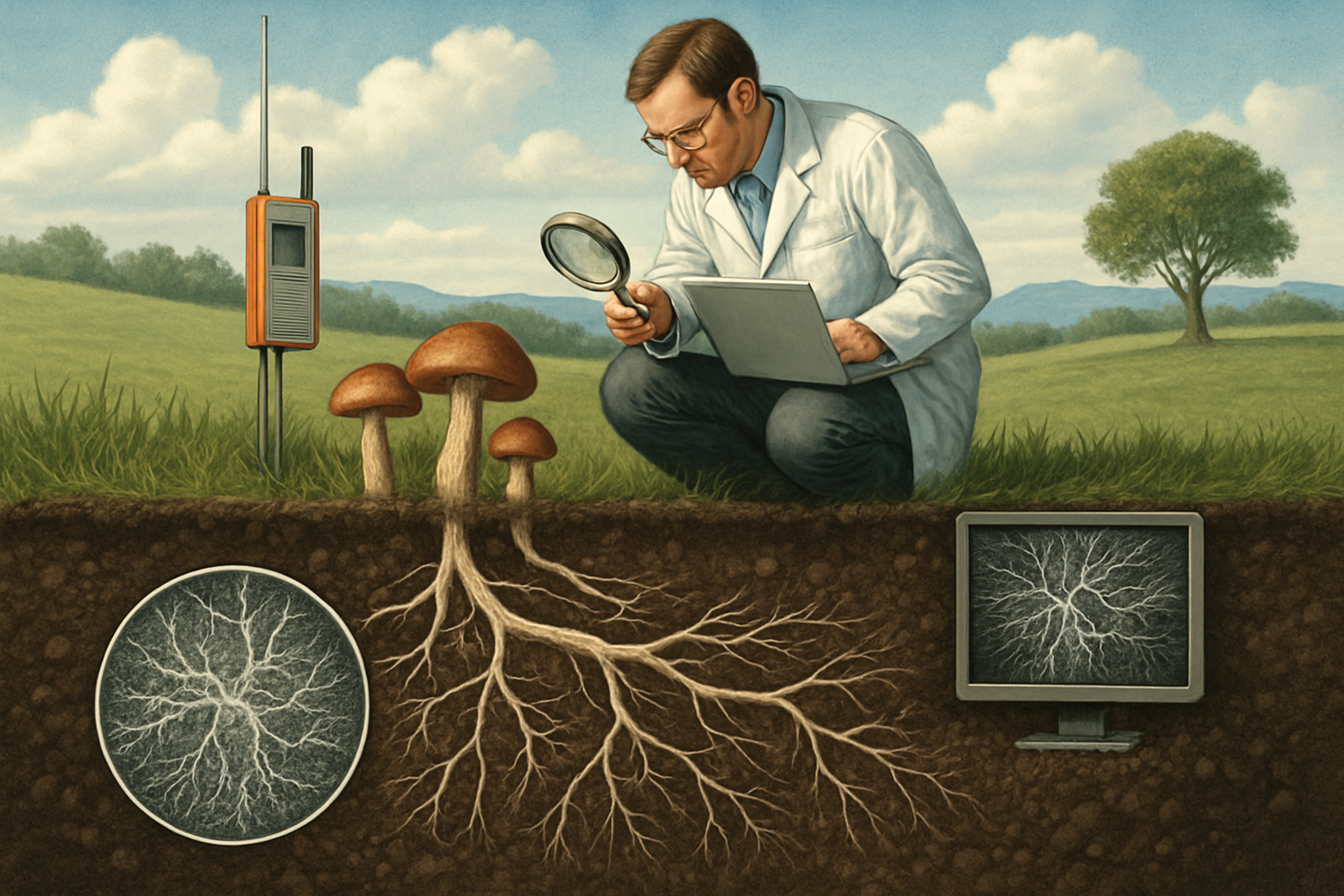

Long before satellites scanned the canopy or researchers measured atmospheric CO₂, an unseen network wove its way through forests and meadows alike. This web of fungal filaments-mycelium-links plant roots in a vast underground marketplace, trading water, nutrients and chemical signals. Today, as ecosystems buckle under extreme weather and shifting precipitation patterns, ecologists are excavating this ancient system for solutions to modern climate woes.

Underpinning the science is the symbiosis between plants and mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi colonize root surfaces or weave directly into root cells, extending their reach far from the plant’s physical footprint. In exchange for sugars produced by photosynthesis, mycorrhizae unlock minerals-phosphorus, nitrogen, trace metals-from soil particles. Recent meta-analyses suggest that up to 30 percent of carbon fixed by trees flows into fungal partners each growing season. That carbon fuels fungal growth underground and ultimately traps CO₂ in stable soil organic matter.

What was once purely ecological theory is now the focus of cutting-edge research. Teams at a major university used ground-penetrating radar and electrical resistivity tomography to create the first high-resolution maps of mycelial networks in a temperate woodland. Scans revealed sprawling conduits spanning more than 50 meters, connecting old oaks to young maples and even linking distant herbaceous plants. This “wood wide web” appears to distribute resources, cushioning saplings against drought and accelerating post-fire recovery.

At the National Institute of Ecology, scientists have paired sensor arrays with machine learning to track nutrient flows through these fungal highways in near real time. By injecting harmless tracer compounds at specific root zones and monitoring their arrival at distant points, researchers can quantify how swiftly water and phosphorus travel through the network. Preliminary findings show that during seasonal dry spells, fungi reroute moisture from deeper soil layers to surface roots, buffering trees against water stress.

These insights have practical implications for landscape restoration. In one large-scale pilot project, conservationists inoculated thousands of seedlings with native mycorrhizal spores before planting on an erosion-prone hillside. After two summers of intense heat and erratic rainfall, survival rates doubled compared to uninoculated controls. Soil sensors recorded higher moisture retention and microbial activity, indicating a more balanced, resilient ecosystem emerging beneath the saplings.

Beyond local trials, agricultural researchers are investigating mycorrhizal applications for degraded croplands. By restoring fungal partners, soils once stripped by intensive tillage begin regenerating structure, porosity and organic matter. Farmers adopting these techniques report reduced fertilizer needs and improved drought tolerance in cereals and legumes. While results vary by soil type and climate zone, a joint study across five continents found yield increases ranging from 10 to 20 percent in mycorrhiza-enhanced plots.

Technological breakthroughs are speeding these discoveries. Innovations in fluorescent probes now allow in-field visualization of fungal hyphae under portable microscopes. Researchers can tag phosphorus molecules with non-toxic dyes and watch them move through living mycelium toward plant roots. Drones equipped with hyperspectral cameras detect subtle shifts in canopy reflectance that correlate with belowground fungal activity, offering a noninvasive way to monitor ecosystem health at landscape scales.

Tracing carbon pathways is equally critical. Soil ecologist teams are deploying stable isotope labeling-introducing ¹³C or ¹⁵N into plant tissues-and following those isotopes into fungal biomass. These experiments reveal how much carbon stays locked in mycelial networks and how long it persists before decomposing. Understanding these dynamics is essential for integrating fungal processes into global carbon models, potentially closing gaps in our forecasts of future climate scenarios.

Despite promising advances, challenges remain. Fungal diversity is immense-estimates range from 2.2 to 3.8 million species-and only a fraction are well studied. One grassland study uncovered more than 500 distinct fungal taxa in a single square meter, many with unknown functions. Introducing non-native inoculants risks disrupting local communities, so researchers emphasize sourcing fungi from nearby undisturbed habitats.

Policy and regulatory frameworks are also catching up. In some regions, mycorrhizal products are classified as soil amendments, requiring minimal oversight. Elsewhere, they fall under biopesticide regulations, entailing lengthy approval processes. Industry groups and academic consortia are collaborating to standardize efficacy tests and quality control protocols, ensuring that products deliver viable spores and hyphal fragments capable of colonizing roots.

Community science projects are filling knowledge gaps too. Volunteers armed with DIY soil kits collect samples from backyards, parks and farmlands, uploading DNA barcoding data to open repositories. These crowd-sourced databases help map fungal diversity across climates and land uses, identifying areas where critical mutualisms may be vulnerable. Such efforts not only democratize ecological research but also foster public awareness of the underground networks sustaining life on Earth.

Looking ahead, the integration of fungal highways into climate action plans could reshape conservation and agriculture. Some experts envision ‘mycoengineers’-specialists who diagnose soil network health and prescribe fungal formulations tailored to specific ecosystems. These fungal toolkits might include drought-resistant strains for arid zones, phosphorus-mobilizing species for nutrient-poor plots, or endophytes that boost plant immune systems against pests.

Financial incentives are already emerging. Carbon credit markets that accept soil sequestration protocols are starting to recognize fungal contributions. Pilot programs in Europe and North America reward land managers for practices that enhance mycorrhizal density and biodiversity. As verification methods improve, fungal network management could become a mainstream instrument in national greenhouse gas inventories.

The promise of mycelial highways extends beyond climate mitigation. These networks serve as communication channels, transmitting warning signals when pests or pathogens attack. Healthy fungal communities bolster ecosystem resilience, reducing the severity of disease outbreaks and promoting recovery after disturbances. By preserving and enhancing these subterranean lifelines, humans may safeguard biodiversity and maintain the ecological balance on which all species depend.

In a time when many solutions involve massive infrastructure or high-tech interventions, the quiet work of fungi offers an elegant alternative. It reminds us that resilience often lies in partnerships cultivated over eons. As researchers continue to unveil the mysteries of the fungal frontier, one thing becomes clear: the future of climate adaptation may well depend on the smallest architects beneath our feet.